Over the course of his five decades-long filmmaking career, David Cronenberg has become best known as the pioneer of “body horror.” But his artistic contributions far exceed the creation of a niche microgenre. Even at their most fantastical, his films expose a universal darkness within the human psyche. Cronenberg’s best films are mirror images of our most heinous desires, as well as the consequences of attaining them. Here are his five best works.

Dead Ringers (1988)

With a significant lack of focus on body horror, Dead Ringers delves into the duality of humankind, as represented by its two protagonists, twin gynecologists Beverly and Elliot Mantle. Beverly—the awkward, sensitive twin—is initially painted as “the good one,” a perception the viewer loses when a wicked arrangement he has with his brother is revealed.

As the film progresses, the two spiral into the throes of drug addiction, and their codependency becomes increasingly toxic, resulting in a horrific ending that only Cronenberg could have concocted. Its realism—especially with regards to addiction—make it one of the most disturbing films on this list. This is only augmented by Jeremy Irons’ harrowing performance, for which he won the Genie Award for Best Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role.

The Fly (1986)

One of the rare instances in which a remake is better than the original, Cronenberg’s The Fly—based on the 1958 film of the same name—is centered around an eccentric scientist named Seth Brundle (played by Jeff Goldblum), who has invented a device consisting of two pods that can teleport objects between them. To prove the efficacy of his invention, he himself drunkenly enters one of the pods, unaware that a house fly has entered with him. He successfully teleports himself, though his DNA has become merged with that of the fly.

Throughout the film, he becomes more and more mutated into an absolutely disgusting-looking human-fly hybrid, this transformation illustrated by some of the greatest practical special effects ever put to film. Being a Cronenberg film, The Fly is about more than just a human’s metamorphosis into a monster. It is a love story at its core. But, again, being a Cronenberg film, it doesn’t come with a fairytale ending.

The Fly is a perfect example of Cronenberg’s ability to turn the most bizarre extremes of science fiction into art that is reflective of the human experience.

Eastern Promises (2007)

Crime drama Eastern Promises is the most conventional film on this list. But that’s not saying much when it comes to Cronenberg. Starring Viggo Mortensen as an aspiring mobster, the film explores the world of Russian crime, specifically human trafficking. Featuring some of the most brutal violence ever shown to mainstream audiences, Eastern Promises exposes the savagery of the criminal underground in a way that feels more necessary than exploitative. Its relentless bloodshed reaches its peak in the film’s infamous bath house knife fight scene, which Roger Eberrt said “sets the same kind of standard [for fight scenes] that The French Connection set for chases. Years from now, it will be referred to as a benchmark.”

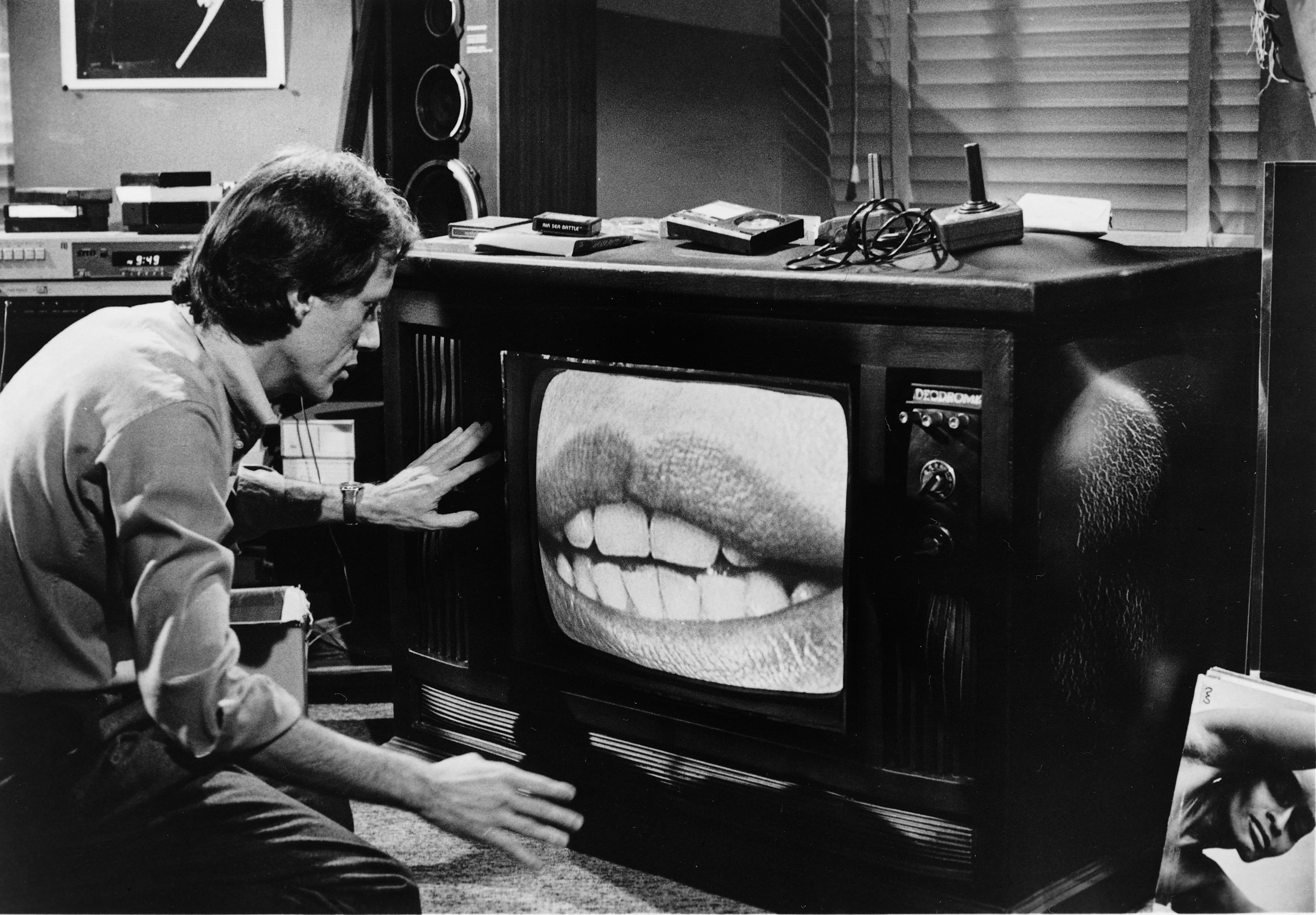

Videodrome (1983)

What appeal do we see in Cronenberg’s depictions of violence and gross-out horror? What repressed parts of our souls do such twisted media speak to? These are questions Cronenberg himself sought to answer with Videodrome.

James Woods stars as protagonist Max Renn. Referred to by his critics as a “smut pedder,” Renn is the manager of a cable channel that exclusively airs boundary-pushing violent and erotic content. When he stumbles across a pirated broadcast signal airing “Videodrome”—a plotless series containing nothing but the most stomach-turning depictions of real-life torture and death—he is immediately intrigued, seeking to track down the media’s elusive creators. But Renn’s constant exposure to Videodrome warps his sanity, and the film’s realism simultaneously twists into a full-blown nightmare.

Videodrome is open to interpretation, though perhaps it is simply an examination of how our culture’s unending subjection to violence affects the collective psyche. As the film’s secondary character Nicki Brand says, “I think we live in overstimulated times. We crave stimulation for its own sake. We gorge ourselves on it. We always want more, whether it’s tactile, emotional or sexual. And I think that’s bad.”

Crash (1996)

Based on J.G. Ballard’s controversial novel of the same name, Crash is an exploration of overstimulation at the hands of technology. Starring James Spader, it sees protagonist James Ballard endure a near-fatal car accident, which becomes the catalyst for his and his wife’s immersion into a community of car crash fetishists. Its premise is so bizarre that upon its release, it even attracted controversy amongst Cronenberg fans, many of whom failed to see the substance underneath the filth. Among its critics was Francis Ford Coppola, who refused to personally present to Cronenberg an award the film won at the Cannes Film Festival.

Crash’s controversy is only an indicator of its audacity; it is Cronenberg at his most unrestrained.